In the News

Reaching Them When They are Young

At a 2014 congressional briefing co-sponsored by APA, experts say it's critical to prevent substance abuse early on.

By Rebecca A. Clay

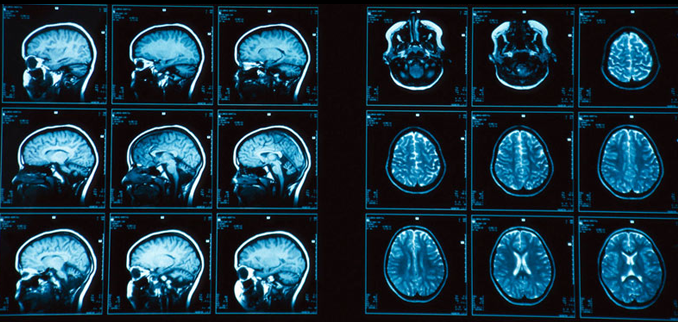

Since the human brain doesn't stop developing until around age 25, abusing alcohol and drugs before that age can result in lasting damage, warned experts at a congressional briefing co-sponsored by APA. Held on Capitol Hill on Oct. 20, "Adolescent Brain Development: Understanding the Impact of Substance Abuse" was sponsored by the Friends of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the Friends of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in cooperation with the Addiction, Treatment and Recovery Caucus, plus many co-sponsors.

In economic terms, said NIDA Director Nora D. Volkow, MD, alcohol, tobacco and substance abuse costs the nation more than half a trillion dollars each year. "Substance use disorders are devastating, but they are theoretically preventable," said Volkow. "That's why targeting adolescents becomes so important because that age group is crucial in our ability to succeed." Just look at what alcohol does to the adolescent brain, said NIAAA Director George F. Koob, PhD. In the short-term, drinking disrupts the brain regions responsible for decision-making, impulse control, memory and anxiety. In the long-term, excessive alcohol use can alter the brain's developmental trajectory and cause lasting cognitive deficits. Plus, said Koob, "the earlier you use and misuse alcohol, the more likely you are to have an alcohol use disorder later in life."

Psychologist Sandra A. Brown, PhD, of the University of California in San Diego, presented research findings showing just how harmful adolescent substance use can be. In one study, for example, she and her team presented information to teens in treatment for alcohol problems who had been abstinent for three weeks. Brown then tested the students on what they'd learned and compared their results with those of peers in the community who hadn't been exposed to alcohol or drugs. She found that while the teens in treatment learned information at the same rate as their community peers, when she tested them 20 minutes later, they remembered 10 percent less than their community peers. That's not just a letter grade difference in performance, she added. The difference can also harm students' self-esteem, their belief that they can succeed in school and their ambitions in life, she said. And the effects can reverberate across a lifetime. In a four-year follow-up, Brown found that neurocognitive functioning was stable among those who stayed abstinent. But among those with continued alcohol use after treatment, there was continued neurocognitive deterioration.

In other research, Brown has followed youth treated for alcohol, marijuana and other substances for more than a decade. When treatment during adolescence was successful, those teens grew to be adults who were just as successful as peers who never had drug or alcohol problems. Teens whose treatment wasn't effective had much worse outcomes, with more legal problems, lower educational and occupational attainment and more health problems than their peers.

Still unanswered are important questions, such as how the timing, dose and duration of alcohol and drugs affect the brain and how the adolescent brain recovers, said Brown. Federally funded researchers, including those participating in the National Consortium on Alcohol and Neurodevelopment in Adolescence -- a five-site study of 830 adolescents that Brown coordinates -- are now tackling such questions.

Noting that most studies of youth are cross-sectional or short-term, Brown urged policymakers to support long-term research. "It's only through longitudinal research that we can fully understand the impact of alcohol and other drugs on human brain development," she said.

Rebecca A. Clay is a journalist in Washington, D.C.